Health

Postcard from bed: Dealing with chronic pain and invisible disability

As Rachael Mogan McIntosh well knows, living with chronic pain means plans can fall apart without warning, but the constant adjustments come with valuable perspective.

By Rachael Mogan McIntosh

I’m on a 4-day writing retreat, gloriously alone, in a tiny flat with a view of the Sydney Harbour Bridge. It’s a big deal to carve this time away from my family and work responsibilities and I have huge plans. But on day 2, something unzips and dismantles deep and low in my back and I’m suddenly unstable; my writing retreat tanked almost as soon as it began.

Welcome to Chronic Pain Land, where any good day can turn on a dime. Other chronic-pain sufferers will know the disability-mathematics I’m working out now: what’s coming next? How bad is this? Is it just a blip or a full dismantling?

Never alone, yet so alone

Australian broadcaster Monty Dimond recently told the Imperfects podcast about her diagnosis of chronic migraine, which causes debilitating dizziness and bouts of pain lasting up to 6 weeks at a time. “People think it’s just a headache,” Dimond said. “But I cannot leave my room. And it’s so lonely being sick.”

British author Chris Bridges wrote a character with a chronic illness in his novel Sick to Death, basing the details on his own experiences with multiple sclerosis. He has good days, but when his MS fatigue kicks in, he says “I feel like I’ve drunk half a bottle of Prosecco on a hot afternoon.” All of the hangover, none of the fun.

Complications from hip surgery led to a chronic pain condition for Australian journalist and presenter Osher Gunsberg, a situation further layered because, many years sober, he did not want to become reliant on pills. He went hunting for other ways to manage his pain, recording his findings in the documentary Osher Günsberg: A World of Pain, still available to watch on SBS.

An invisible disability

Like Gunsberg and Dimond, who explores her experience of chronic pain in her podcast Ichronic (‘if you don’t laugh, you’ll cry!’) and novelist Bridges, I’ve tried to understand my experience through my writing. My back pain comes courtesy of 2 fusion surgeries and a gnarly speedboat accident and plays something of a supporting character in both my books Pardon My French and Mothering Heights.

I’ve limped to the bed now, turned on the electric heating pad and taken some deep breaths to quell the rising panic and frustration. Chronic pain is sometimes called an invisible illness, because those of us who experience it get used to slapping on a smile and leaving the party early to recover in bed.

While it’s hard, sometimes, to explain these ‘dynamic disabilities’ that ebb and flow unpredictably, we do know there are a lot of us. In a 2021 ABS snapshot, over three-quarters of Australians had at least one long-term health condition and almost half had at least one chronic condition.

Chronic pain has main-character energy

Pain affects the whole family system. “As your sleep gets affected, your mood gets affected, and you become cantankerous.”’ says Gunsberg. “If there was something cute and fun happening,” his wife Audrey adds, “it was like it didn’t touch him, because he was so consumed by the pain. It was difficult to be around him.”

Pain can be a third person in my marriage too. I sometimes think of it as a polyamorous set-up with a real cow of a sister-wife. It’s hard to know whether to soldier through, stoic and silent, a tactic that isolates you from others; or to share what’s happening, leaving you feeling like a whinger. The middle ground can be hard to find, for partners as well as the sufferer themselves.

It comes down, often, to energy. People in the disability community talk about ‘spoons’ as a metaphor for the amount of energy one has in a day. Pain can steal many, many more spoons that a person might have for a given day, and sometimes one must borrow ‘spoons’ from the next day, risking the burnout that comes when there’s nothing left in the cutlery drawer.

Beyond good humour, what helps?

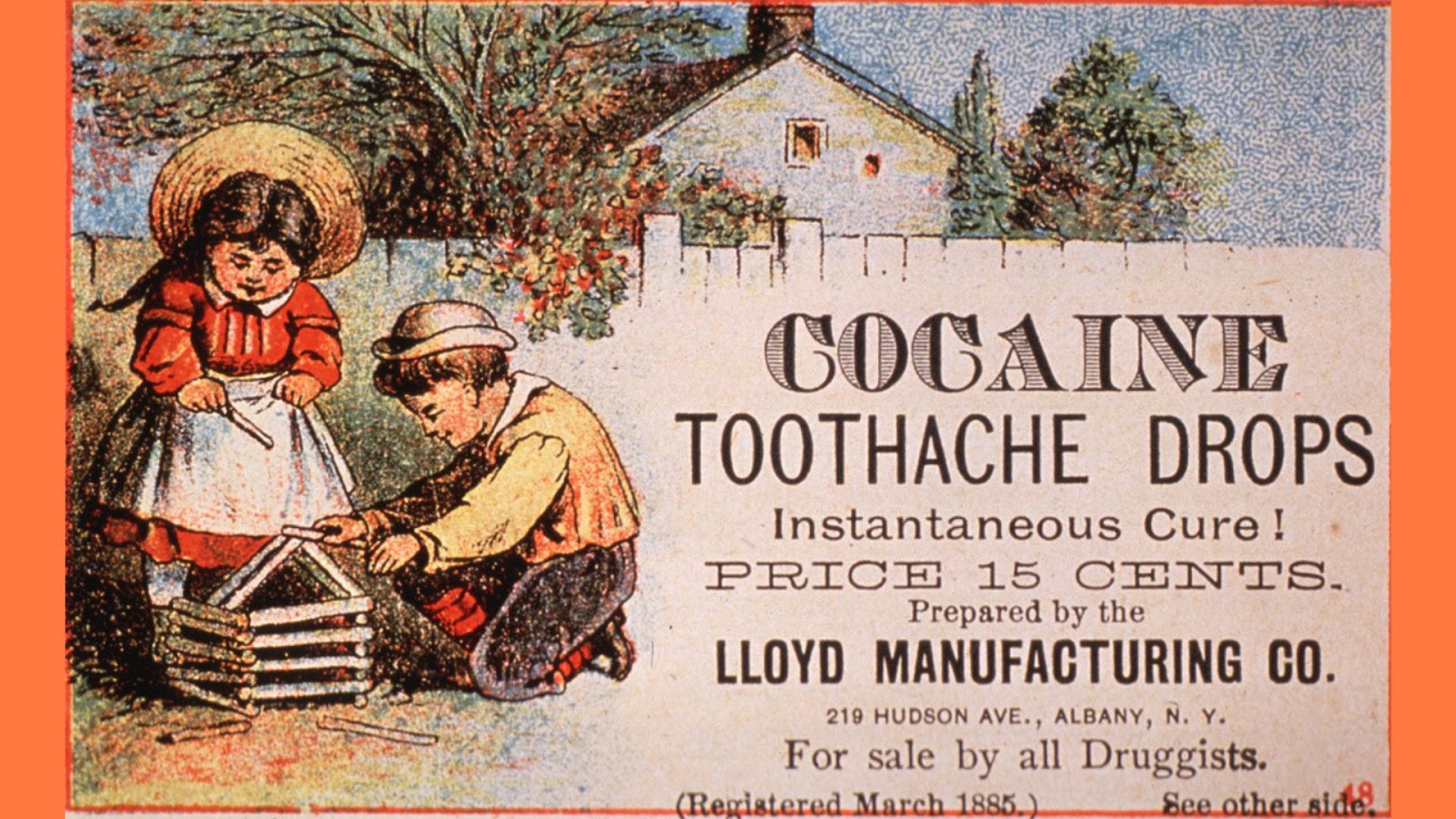

Using medications to treat pain is a strategy that goes back to the days of using cocaine, laudanum and heroin, but there are many other ways medical specialists and researchers are trying to understand the way our brains process pain.

Exercise has long been advised to manage chronic pain without medication. “According to current research, exercise for those with chronic pain can improve pain severity and physical function, and consequently, quality of life,” said Dr Roma Forbes in an article for Faculty of Health and Behavioural Sciences at the University of Queensland. “However, as the experience of living with chronic pain is different for everyone, it is important that exercise and other management strategies are individualised to your ability and your lifestyle.

New research from the University of South Australia shows that eating nutritious food can also significantly reduce chronic pain.

“While weight loss helps many people, this study suggests that improving diet quality itself also eases the severity of people’s pain. This is a very hopeful finding for people living with chronic pain,” said lead researcher and PhD candidate, Sue Ward.

Retraining our brains to process ‘sensation’ in a different way could also play a role. For example, UNSW and NeuRA researchers have found that pain intensity could be significantly reduced through emotional regulation techniques as an effective therapy for chronic pain.

The hidden gifts of living with pain

Like anything difficult that we must grapple with, pain holds hidden gifts. In one of my books, I mused on how developing the skill of zoning out – the underrated art of being Not Present In The Moment – in order to escape an uncomfortable reality was a surprisingly helpful mothering tool when my children were small.

The children may have been dragging at my legs, wailing like banshees, but in my mind, I was on the shores of Lake Como, while an Italian manservant handed me an espresso martini and winked sensually. (Gianni was extremely handsome but completely smooth between the legs like a Ken doll; wanting only to worship me and making no sexual demands whatsoever.)

Those of us in this strange chronic pain club develop a certain compassion for frailty, a nimble capacity to innovate hacks and workarounds, and a hard-won patience for those times when things go wrong.

I’ve lost most of the day, but by the afternoon, I’m able to walk around the flat again, although I am moving like an old Labrador. I’m relieved as I adjust my plans, removing long walks and hours at the desk, instead settling for gentle stretches and working while flat on my back. I can still see glimpses of the Harbour Bridge from here. I’ll make it work.

Citro may receive a small commission at no cost to you on any orders placed using the book links in this article.

The information on this page is general information and should not be used to diagnose or treat a health problem or disease. Do not use the information found on this page as a substitute for professional health care advice. Any information you find on this page or on external sites which are linked to on this page should be verified with your professional health care provider.

Feature image: iStock/AsiaVision

More on managing chronic conditions: