Lifestyle

Cleaning out Mum’s house broke my heart and filled it at the same time

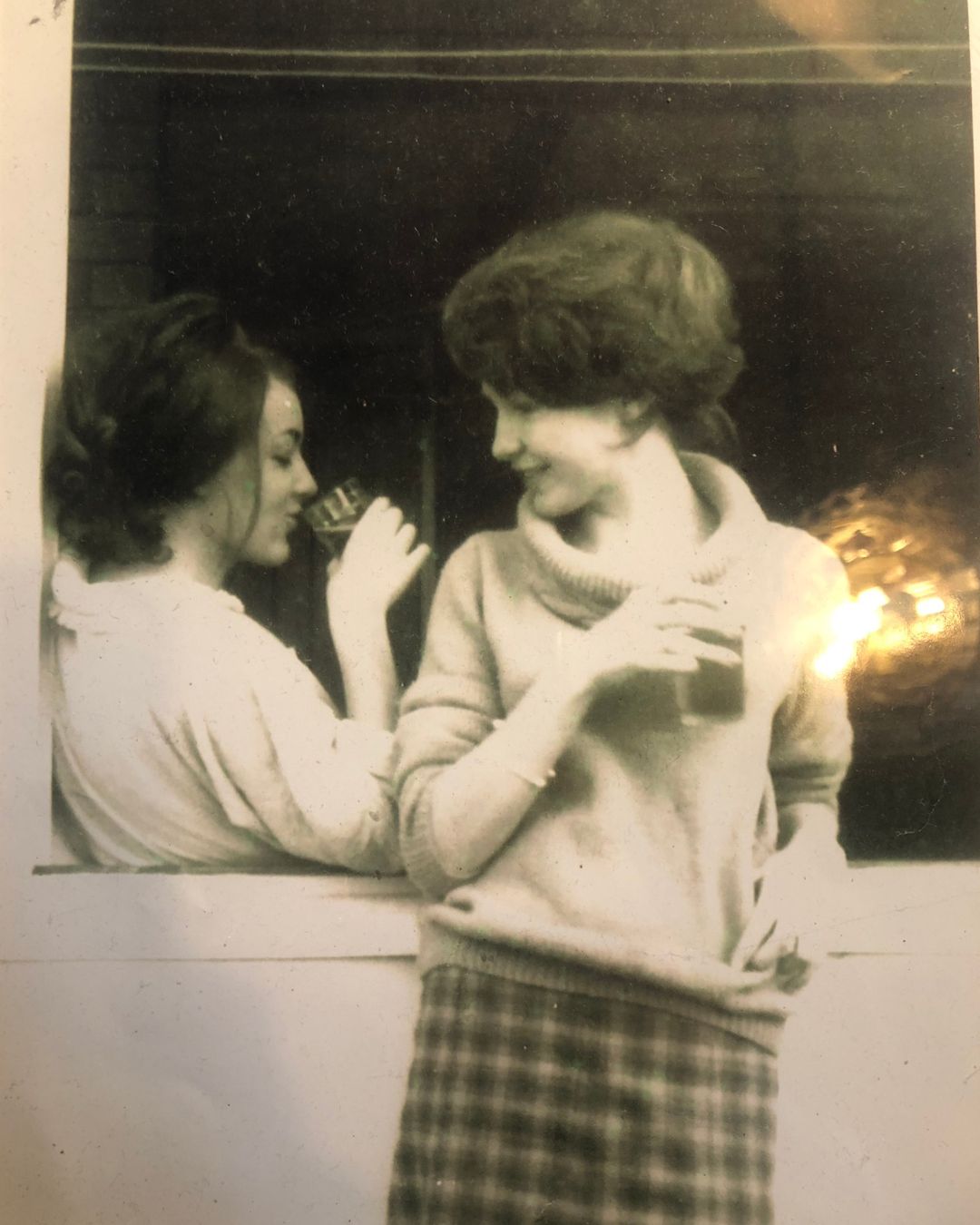

When her mum, Chris, passed away, the task of sorting through a lifetime of keepsakes fell to Rachael Morgan McIntosh. In the quiet work of packing up a house, she uncovered the ordinary, everyday objects that still carry her mother’s stories.

By Rachael Mogan McIntosh

My mum died last year. (I’m still not used to saying that.) The job of sorting out her many baskets of papers and pictures has fallen to me. I find photo after photo capturing her in the full-skirted, tight-waisted frocks of the late 50s, picnicking in Hyde Park with her friends from the Health Department. That’s where she met my Dad Frank. He threw up on her shoes during one of their wild public-servant parties, and Mum, so shy and nurturing, took care of him. She liked the combination of his gruff demeanour and the thin book of Banjo Patterson poetry in his back pocket.

Mum sewed all those dresses on the dining room table after dinner, because buying dresses ‘off the rack’ wouldn’t become a common practice until the late 60s. This is one of the facts that astonish her grandchildren, like the outdoor toilet of her childhood, or the way she had to hide her growing belly from the bosses at the Health Department. Girls were required to leave work once wed, but while the department turned a blind eye to marriage, a pregnancy was beyond the pale.

Try this: 11 of our favourite tools and apps to record your life story

Finding Little Nanna

Amongst Mum's papers, there are those of my grandmother, Little Nanna, captured in several snapshots striding along city streets in wasp-waisted jackets and jaunty hats, like a young Kate Hepburn. She had dreamed of being a ‘flapper typist’ as she watched the Harbour Bridge being built – arches reaching for each other from her school classroom windows – but she settled for marriage and six kids in a redbrick house in Sydney with an outdoor toilet (her mortgage receipt, in copperplate handwriting, reads ‘870 pounds’). Little Nanna ran her washing through a mangle and posted newspaper pages onto a nail in that outdoor dunny.

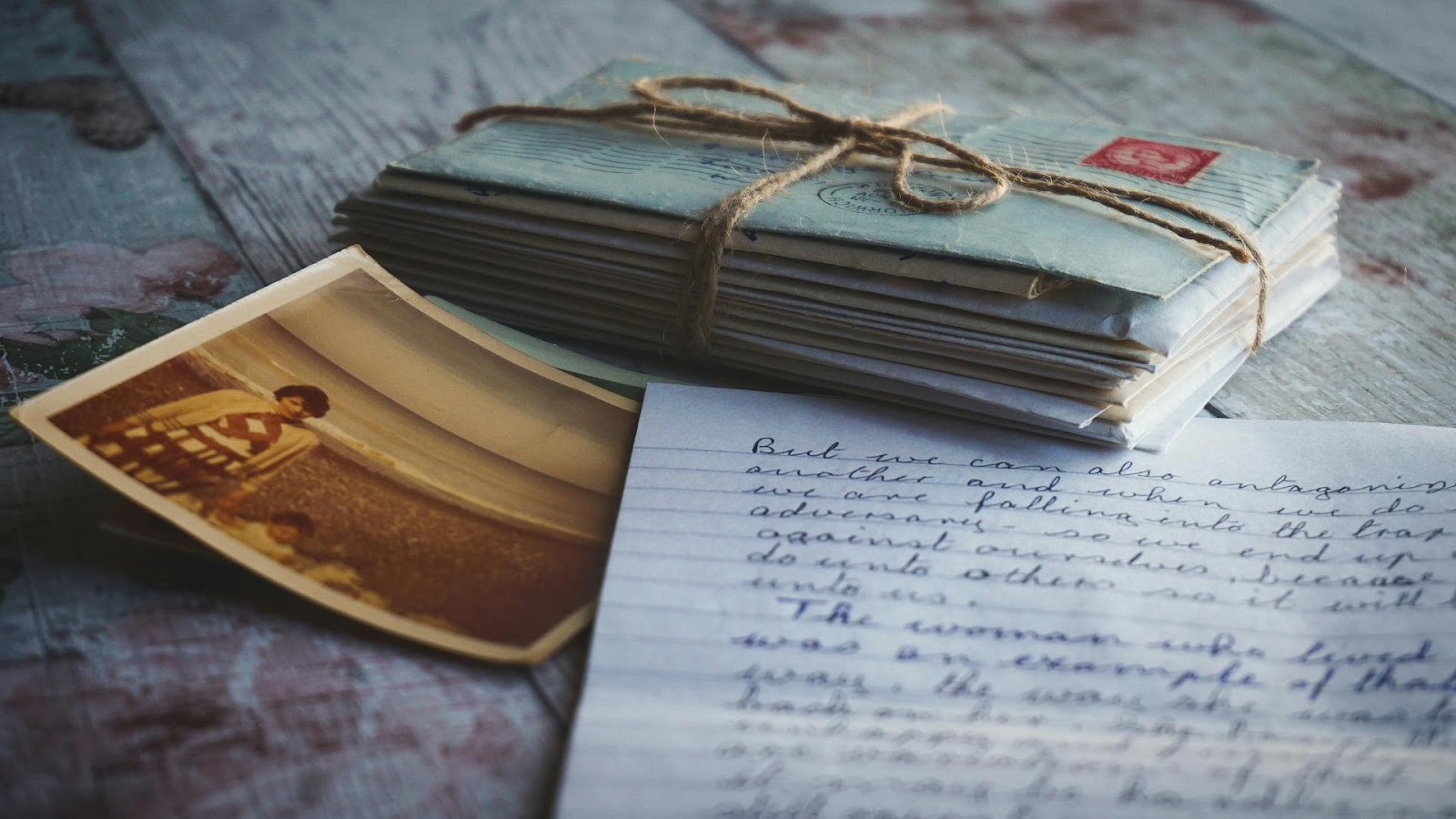

A small leather-bound daybook belonging to her brother George turns up. I have a George too, but never realised that she had a namesake great-great-uncle. I don’t know what to do with this little book, almost empty other than a couple of phone numbers and some window measurements.

There are endless newspaper clippings and recipes torn from magazines, handmade birthday cards from my mother’s childhood and my own, medical reports and faxes home from my sister Sam and I, living in London and beset with constant boyfriend troubles. I eyeball every one, save a selection, but must bin the rest, a process that is both pedestrian and heartbreaking. At the end of a week of this, I go to bed with a splitting headache.

Packing up a life

The house is getting packed up too, as Dad prepares to move to a nursing home. My sister Sam and I rope the grandchildren in.

Surrounded by bubble wrap and boxes, they pack crockery and frames and books for the op shop, just as Sam and I did for Little Nanna so many years ago. Mum’s overflowing cupboards were just like her own mother’s; including the ‘present drawer’, full of trinkets she never got to disseminate amongst the grandchildren. We find a tape recording made in our childhood and play our tinny, toddler selves for our daughters. Heartbreaking, pedestrian.

I list furniture on Marketplace for Dad, including the dining table from our childhood. Sam remembers the family dinner in which I disgraced myself with Father Tom, Dad’s brother, a priest and our favourite uncle.

I was about nine, had heard a new joke at school and waited, giddy, for the perfect pause in conversation in which to drop it. Tom was funny, and I knew he would be delighted.

‘Close your legs, Tom,’ I said into the silence. ‘It’s rude to point.’

Adult faces swivelled to me in horror, but the joke wasn’t finished.

‘You too, Mum,’ I said. ‘I don’t like your hairstyle.’

I remember Dad roaring ‘go to your room!’ and Sam remembers my look of shock. I didn’t even understand the joke, but I trudged up the stairs anyway; a failed comedian, and not for the last time.

Two generations and we’re gone

Father Tom is gone now, too, dying young of a heart attack in Rome, and the house is nearly empty, with only a week left before Dad moves to his new life. I’m taking care as I sort the last of the photos and papers.

We only really exist, they say, in the hearts and minds of those two generations below. When I’m gone, nobody will be able to bring to life the fading grin of Nana Goodie, my mum's beloved grandmother, a prankster who scribbled over the faces of neighbours she disliked in the photo album and wrote ‘borrow these and you die!’ on the spine of her knitting pattern folder.

I decided to use George’s diary, my scribbled notes for my current novel-in-progress sitting on the faded yellow pages beside his window measurements. I love the idea that our lives are intersecting in some tangible, heartbreaking way. I don’t want this notebook lost again in a tumbled pile of papers, and I love that it links me to Mum, who I miss so very, very much.

Feature image: Courtesy of the author

More ways to connect: